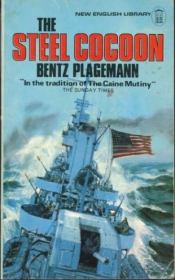

Bentz Plagemann - The Steel Cocoon

| Название: | The Steel Cocoon |

Автор: | Bentz Plagemann | |

Жанр: | Морские приключения, Военная проза | |

Изадано в серии: | неизвестно | |

Издательство: | неизвестно | |

Год издания: | 1957 | |

ISBN: | неизвестно | |

Отзывы: | Комментировать | |

Рейтинг: | ||

Поделись книгой с друзьями! Помощь сайту: донат на оплату сервера | ||

Краткое содержание книги "The Steel Cocoon"

Life aboard the WW II destroyer AJAX whose routine is flawed by an officer-enlisted man gulf, autocratic actions, fatal accidents, and men going "Asiatic," even psychotic.

THE sick bay of the destroyer Ajax on her shakedown cruise, the war seemed remote to Tyler Williams. A civilian in the uniform of a pharmacist's mate, Williams was a member of the crew; yet by the special nature of his duties he was a man apart. To whom then did he belong? To his superior, that strange and perhaps dangerous man, Chief Bullitt? To himself? To the men of the crew, so vulnerably dependent upon one another? By the time the shakedown was over and the Ajax was ready for war, Tyler Williams would find his answer. This is a story of the rigorous training, raucous shore leaves and dramatic emergencies that mold men into a fighting crew. With humor, zest and compassion, The Steel Cocoon looks deep into the special world that is life on a Navy ship.Читаем онлайн "The Steel Cocoon". [Страница - 5]

Wearing clean undress whites, he went ashore with the liberty party. In the unchanging gray light, scrub-pine growth struggled up low hills, which seemed not hills so much as piles of glacial moraine. The Navy buildings lay beyond the port community itself, whose few structures, in this land beyond the timber line, looked as if they had been built of orange crates and bits of driftwood.

Williams walked heavily over the stony ground to the recreation building, a large Quonset hut, where beer was to be had. At the long, crowded bar his ration of six cans was given to him all at once, all opened at the same time, and Williams scooped them up gratefully in his arms and made his way to an unoccupied table in a far corner. He sat sideways, with his feet up on the bench, and quietly, in a businesslike way, he began to drink the six cans of beer.

After the third or fourth can he began to hold a conversation with himself. It had been so long since he had spoken outside of the performance of his duty ("Where does it hurt?" "Does it itch between the toes of the other foot, too?") that he had almost forgotten the conversational tone of his voice. He was a fool, he told himself pleasantly, his voice softened and relaxed by the beer, unheard in the general din which filled the echoing, barnlike hall. Any idiot could do better than he was doing. He was almost twenty-six years old, and he had passed other hazards in his life. Couldn't he just mark time, and do his duty, and wait until this damned war was over, without working himself up like a second-string Hamlet?

Well, maybe six cans of beer wouldn't do it. He went back to the bar and scooped up six more, paying no heed to the harried boy behind the bar who wanted to know if he hadn't been there before. Then he went back to his corner bench again and stretched out full length, holding the fresh beer carefully to his mouth. He had read too much, he decided. He had spent too much of his life in libraries. He was a sort of semi-animated encyclopedia who knew Greek verbs and the minor poets of the Restoration, but aside from that —why, hell, boy, he said to himself, you couldn't be relied on to give the right time of day.

At this point the arched ceiling above him began to waver in a curious, sickening way, and he sat up abruptly. He stood up, and unsteadily made his way toward the door.

When he awoke the next morning he sat on the edge of his bunk and tried to hold his head together with his two hands until he could see clearly. It was very early; reveille had not yet sounded. But he was fully, painfully awake, his heart thumping, every nerve on edge.

In a moment he struggled into his clothes, went topside and made his way to the sick bay. There he closed the door behind him and got the jar of powdered coffee down from the shelf, boiled water in a medical beaker, and made himself a cup of coffee. While he was holding the steaming mug to his face with trembling hands, the top half of the sick-bay door was suddenly thrown open, and framed there in the opening was the ruddy, smiling face of Boats McNulty.

"Did you ever tie one on, Doc!" McNulty said.

A flush of color crept into Williams' face and he felt a surprising, involuntary sense of pleasure. No one on the Ajax had ever called him "Doc" before. A medical officer was "Doctor," but "Doc" was the traditional name for a pharmacist's mate, just as "Boats" was for the boatswain's mate, and "Chips" for the ship's carpenter. But no one had called him that before.

McNulty opened the lower half of the door and came into the sick bay. He took another mug from the shelf above the sink and made himself a cup of coffee. His presence changed the whole sick bay. It was suddenly a part of the ship, as the boatswain's locker was a part of the ship, or a gun mount, or the forward hold.

"Ensign Cripps was on the gangway," McNulty said. "He wanted to put you on report, but I talked him out of it. I said we had to handle pill pushers like you with kid gloves during wartime because you could lower the boom on any of us."

"What did I do.'" Williams asked. " "Well," McNulty said with relish, "Clancy and I managed to get you over the side all right, but then you got away from us. You went below and kept punching guys awake to tell them you were going to beat the hell out of them."

"Oh, no," Williams said.

"Kerensky finally slapped you down. You know, friendly-like."

"Oh, no," Williams said again, feeling his jaw.

"Seriously, Doc," McNulty said, "I don't think you could punch your way out of a paper bag, but you sure gave us a lot of fun. That left of yours, Doc," he said, shaking his head sadly. "It would draw flies."

"What happened then?" Williams asked.

"Oh, Kerensky and I carried you to your sack. We undressed you and tossed you in. You smelled like a stinking brewery. Did you leave any beer for anybody else?"

"I don't think so," Williams said.

"We didn't know you had it in you. Doc," McNulty said, with awkward joviality. "We had you down as a kind of one-way guy."

Williams could say nothing. He turned aside, to make himself another mug of coffee.

"It sure made us feel better," McNulty went on. "We sure thought we'd pulled down a bunch of sad sacks in the sick bay, with Claremont and Bullitt and you."

Williams busied himself with making his coffee, his back to McNulty, feeling again that quick sense of pleasure. He had needed to establish some sort of relationship with the men around him. Suddenly McNulty's approval seemed the most important thing in the world. Maybe when his head stopped coming apart at the seams he would know how to acknowledge that.

"What did you do on the beach, Doc?" McNulty asked, in a hearty tone, as if anxious to get the conversation back on safe ground.

"Oh, I was teaching," Williams said automatically, turning back to face him, "and working for my doctor's degree."

McNulty, who had been lighting a match, held it suspended in mid-air. "You mean they wouldn't let you finish up to be a doctor?" he said in amazement. "You mean they just threw a rating at you?" He lighted his cigarette and leaned toward Williams confidentially, his voice filled with that easy compassion and warmth for the underdog, the timid and exploited, which he possessed in such magnitude. "Let me give the skipper the word. Doc," he said. "You ought to be able to pull down better duty than this if you were studying to be a doctor."

Williams laughed, in spite of himself, an act which threatened to unhinge his skull at the temples. "Not a doctor of medicine," he explained. "Medicine isn't my field."

McNulty's expression changed. His eyes narrowed with speculation. Maybe he had quit school after the eighth grade, but nobody laughed at McNulty. "What was your line. Doc?" he asked quietly.

Williams looked at him, at his firm, healthy face, his untroubled eyes, now rather guarded. Some fortunate instinct told him quickly that McNulty would never in this world understand about Spenser and The Faerie Queene, and he chose the lesser of his two interests. "Anthropology," he said.

"Well, whatever it is," McNulty said, "don't Navy men get it?"

"Anthropology is the study of man," Williams said, wishing he had kept his mouth shut. "You take an isolated unit of people —a tribe in the jungle, a remote Indian village —and you study everything about them. Their relationships. --">Книги схожие с «The Steel Cocoon» по жанру, серии, автору или названию:

|

| Фредерик Марриет - Морской офицер Франк Мильдмей Жанр: Морские приключения Год издания: 1992 |

|

| Григорий Андреевич Карев - Синее безмолвие Жанр: Морские приключения Год издания: 1968 |

|

| Хэммонд Иннес - Корабль-призрак Жанр: Морские приключения Год издания: 2014 |