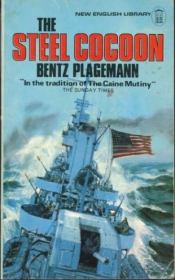

Bentz Plagemann - The Steel Cocoon

| Название: | The Steel Cocoon |

Автор: | Bentz Plagemann | |

Жанр: | Морские приключения, Военная проза | |

Изадано в серии: | неизвестно | |

Издательство: | неизвестно | |

Год издания: | 1957 | |

ISBN: | неизвестно | |

Отзывы: | Комментировать | |

Рейтинг: | ||

Поделись книгой с друзьями! Помощь сайту: донат на оплату сервера | ||

Краткое содержание книги "The Steel Cocoon"

Life aboard the WW II destroyer AJAX whose routine is flawed by an officer-enlisted man gulf, autocratic actions, fatal accidents, and men going "Asiatic," even psychotic.

THE sick bay of the destroyer Ajax on her shakedown cruise, the war seemed remote to Tyler Williams. A civilian in the uniform of a pharmacist's mate, Williams was a member of the crew; yet by the special nature of his duties he was a man apart. To whom then did he belong? To his superior, that strange and perhaps dangerous man, Chief Bullitt? To himself? To the men of the crew, so vulnerably dependent upon one another? By the time the shakedown was over and the Ajax was ready for war, Tyler Williams would find his answer. This is a story of the rigorous training, raucous shore leaves and dramatic emergencies that mold men into a fighting crew. With humor, zest and compassion, The Steel Cocoon looks deep into the special world that is life on a Navy ship.Читаем онлайн "The Steel Cocoon". [Страница - 4]

McNulty rarely smiled, and seldom raised his voice. He did not need to. He was never out of the range of worshiping young eyes. The merest turn of his head would bring two or three seamen to his side, but if it was anything in particular he wanted done he would look over the heads of the others for "Stud" Clancy. "Where's my boy?" he would say. "Where's my boy, Clancy?"

And, "Yes, Boats," Clancy would say breathlessly, coming on the double. "I'm here, Boats. What can I do for you. Boats?"

From the tone of Clancy's voice, and the open look in his clear, boy's eyes, it was obvious that he wanted to be asked to do something really worthy, such as scrub the deck with a hand brush, or paint the whole ship, singlehanded, before sundown, just to demonstrate to every man on board that he, Stud Clancy, was good enough to be McNulty's boy.

When the Ajax had left Norfolk, after the commissioning, McNulty could be found in the afternoon at the boatswain's locker, or at the forward hold, or, in fine weather, out on the open forecastle, with his boys in a circle about him, while they earnestly tried, with solemn faces and stubborn fingers, to tie a Turk's-head knot, or to make a lanyard like the one McNulty wore around his neck. On this lanyard McNulty proudly wore his badge of office, his boatswain's pipe, which he had touched here and there with lead, and molded with his fingers until it produced for him his own sweet, sad note, his own personal cry of discipline, defiance and joy in the face of life. And here McNulty counseled his boys, answering their questions gravely, so that no boy was ashamed to ask any question of him.

Walking on the deck, Williams would see this group in the sun, and his steps would lag a little, almost against his will. Sometimes McNulty would look up with one of his rare smiles, and say, "Come on, sit down. Even a pill pusher ought to know how to tie a few knots."

Half angry, half amused, Williams would smile and pass on, saying he had work to do. Damn it all, he was too old to be McNulty's boy!

CHAPTER 2

LIFE ABOARD the Ajax required adaptability, a love of discipline for its own sake, and an instinctive sense of the inevitable, so that a man would find nothing strange, for example, in being required to sleep in a bunk directly below a length of steam pipe, as Williams had to do. A man suited to that world knew where he belonged, but Tyler Williams couldn't find his place; he kept bumping his head on the steam pipe.Still, he kept his days full. He worked hard. Although Bullitt never acknowledged his industry with even a hint of approval, he was scornful if Williams was too solicitous about the welfare of the men. When Billy Becker, the yeoman striker, Sullivan's boy, was taken off the watch list because he had a severe cold with a temperature of one hundred and three, Williams took him a bowl of soup. A strong wind was blowing off Cape Sable, and Williams lost the first bowl of soup he started out with. The wind lifted it right out of the bowl; he saw the mass of it suspended for an instant in the air before it was flung over the side. He went back to refill the bow'l, and this time he put a heavy crockery plate on top. Bullitt met Williams when he came back with the tray. "They have finger bowls in the officers' galley," he said. "Why don't you take him one after the soup?"

Chief Radioman Benson heard the remark in passing. "Boy," he said, shaking his head, "there's a guy who is really asking for it."

It was true that Bullitt was not very popular in the chiefs' quarters. Only Benson and Chief Boatswain's Mate Kronsky had, like himself, worked themselves up from the lowest rating. Winslow, the chief quartermaster, Calder, the chief machinist's mate, and Tomkins, the supply chief, were civilians who had been given the rating of chief petty officer because of their peacetime background and experience. Presumably, this division should have created a balance, without friction, but Bullitt had thrown it off. Benson was young for a chief in the regular Navy, and it was a sensitive point with him. Bullitt enjoved baiting Benson, who, in return, hated Bulhtt.

Kronsky, like many another old boatswain, had a vague dislike for members of the Hospital Corps, regarding nursing and hospital administration as the province of women. However, he generally put up with the men who did this work. But Kronsky had become fond of Chief Winslow, the quartermaster, who had come to the Navy from the Merchant Marine. When Bullitt had sneered at the Merchant Marine as unmilitary and unheroic, he had alienated Kronsky.

That left Tomkins and Calder, and for them Bullitt reserved his special contempt. Tomkins, the young supply chief, had worked in the catering department of a large hotel. He did an excellent job; if the Ajax was a "happy" ship, as indeed it was, a not inconsiderable factor involved was the quality of the food served. Calder, the chief machinist, had had some practical engineering training, and the Navy had sent him to damage-control school. He was an extremely important member of the crew of the Ajax.

Both Tomkins and Calder were fair, confident young men, who laughed a great deal. I hey were the sort of men who grow up in the suburbs of our large cities, and go to good high schools; excellent examples of middle-class America. No one knew what Bullitt's background had been, but after nineteen years in the Navy he had become so indoctrinated in the stratification of Navy life, where a man is either an officer or an enlisted man, an aristocrat or a commoner, that he could find no ground on which to meet Tomkins or Calder. Their open, happy, untroubled faces irritated him. Their easy, relaxed way with officers made him angry and jealous. He baited them with questions, trapped them by their ignorance of Navy ways, and then laughed sardonically at their confusion and anger. "Oh, so it's 'dinner,' is it?" he would say, when Tomkins was discussing the day's menu with Butler, the cook. Or, to Chief Calder, "Did you say 'pick that up off the^oor'?" He shook his head. "You civilians may win the war," he said. "But it will take years for the Navy to recover."

The Ajax arrived at Argentia during the time of the midnight sun, when, day or night, it was never wholly light nor wholly dark. With a sister fleet of destroyers, they rode anchor in the harbor, in an endless world of gray water, off a bleak, gray shore. Suddenly it was impossible to imagine that anything else existed, as if they had managed to sail off the edge of an ancient map into the unknown world.

On the morning of the first day, a liberty list was posted and Williams saw his name there. In the late afternoon, when Bullitt had finally left him alone, he closed the door of the sick bay, got out his shaving gear, and propped a small hand mirror above the sink. In the glass even his own lean, intelligent, not unpleasant face seemed unfamiliar to him. His past life, his study, his teaching, all seemed part of life in another incarnation. The Navy had run over him with its machinery until everything else was flattened out of him, as if its indifference to and ignorance of the values by which he had lived had suddenly rendered those values meaningless. Perhaps here lay the distinction that separated the civilian from the military man. A man who would choose a military life for a career was a man who welcomed or needed in some way the security of a --">Книги схожие с «The Steel Cocoon» по жанру, серии, автору или названию:

|

| Майкл Поуп - Королевский корсар Жанр: Морские приключения Год издания: 2002 |

|

| Альфред Лансинг - Лидерство во льдах. Антарктическая одиссея Шеклтона Жанр: Путешествия и география Год издания: 2014 |